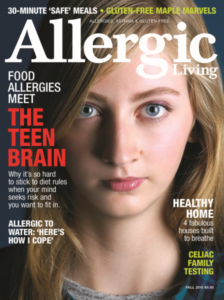

23 Jan Food Allergy Meets the Teenage Brain

Teens, Peer Pressure, and Allergies

In adolescence, teens face peer pressure — all the while their brains are developing and their hormones surging. Adding food allergies to the mix ratchets up the risk-taking potential, since not all teens willingly speak up about their food triggers. But as Allergic Living finds in this special report, there is much that parents and peers can do to help allergic teens navigate the sometimes treacherous path to adulthood.

In adolescence, teens face peer pressure — all the while their brains are developing and their hormones surging. Adding food allergies to the mix ratchets up the risk-taking potential, since not all teens willingly speak up about their food triggers. But as Allergic Living finds in this special report, there is much that parents and peers can do to help allergic teens navigate the sometimes treacherous path to adulthood.

SYDNEY Harris, a self-assured, 19-year-old college student, wasn’t always so comfortable with her food allergies. When she was diagnosed with severe allergies at the end of eighth grade, she had to “navigate through a whole new world of challenges.” The following year, she had a tough time finding the support she needed at her high school in Barrie, a city north of Toronto. This was in part because her triggers were not among the top eight allergens, and many people found it difficult to understand her particular allergies. “I didn’t want to be different,” she remembers. “I would leave the house without an EpiPen, or put myself in situations where I was at risk. I didn’t want to accept that I had food allergies.” As a result, Sydney experienced several allergic reactions, at school, home and work.

The day that changed her perspective came right before winter break in 11th grade. During lunch, she walked to a Chinese restaurant with a group of friends. She didn’t check any of the ingredients or mention her allergies to the staff, and by the time she returned to school, she was in “a full-blown anaphylactic reaction.”

Fortunately, one of Sydney’s friends rushed for a teacher, and the school called an ambulance. After three shots of epinephrine and the rest of the day at the hospital, she recovered — but the episode terrified her. “It was the most severe reaction I’d had and the one where I felt closest to death,” she says now, calling this her “food allergy wake-up call.” You don’t need me to tell you that Sydney was lucky.

Yet Sydney’s story is instructive. It illustrates the many challenges faced by food-allergic teens: strong social pressure to fit in; increasing amounts of time spent with friends and away from adults; environments that don’t always support them in the ways they need; and questionable decisions that don’t always fall in line with what these kids actually know. It’s hard enough navigating adolescence, but simultaneously managing a serious health condition adds an extra layer of complexity.

Sydney Harris

Parents of food-allergic teens — and parents of soon-to-be teens, like me — have reason to worry. While deaths from severe anaphylactic reactions are uncommon, when they do occur, we know it’s most often among adolescents and young adults, particularly in reaction to peanuts and tree nuts. Certainly not all teenagers take risks when it comes to their allergies, but several commonalities emerge among those who do.

A 2006 survey of adolescents and young adults with food allergies determined that 17 percent of its participants were at “high risk” because they did not always carry epinephrine and ate foods that “may contain” their allergen. Three years later, a bigger survey of food-allergic college students at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor found that only 21 percent of participants said they owned an auto-injector. Also concerning was the large number of students — 60 percent — who reported a previous allergic reaction (though not anaphylaxis) but also said they continued to willingly consume their food allergen.

Of course, it’s not just teens with food allergies who take dangerous risks. We know adolescents are more likely than other age groups to experiment with alcohol, cigarettes and illegal drugs. Teen drivers are nearly three times more likely than those over the age of 20 to be in a fatal crash, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As developmental psychologist and Temple University professor Laurence Steinberg writes in Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence, “In virtually all arenas, adolescents take more risks than either children or adults, and the incidence of risky behavior usually peaks somewhere during the late teens.”

Is this because teens have “lost their minds” or “gone crazy”? Despite how our culture tends to view teenagers, the answer is “no.” To understand what’s actually going on, it’s helpful to turn to research in neuroscience, which has been rewriting our understanding of adolescence and the incredible changes that take place in the teenage brain.

Inside the Teenage Brain

Neuroscientist Abigail Baird: Teens do have impulse control.

Advances in scientific knowledge about brain development during adolescence have shown us that the human brain continues to grow for much longer than we previously thought. In fact, the years of adolescence — which many experts now define as starting at age 10 and lasting until the mid-twenties — is marked by “heightened neuroplasticity,” a term used to describe the brain’s potential to change through experience. During puberty, the brain has a far greater sensitivity to the influences of social environment than during middle childhood or adulthood.

It’s a time when the brain is not growing as much as it’s being reorganized. Steinberg explains that nearly all of the changes take place in the “regions that regulate the experience of pleasure, the ways in which we view and think about other people, and our ability to exercise self-control.” During adolescence, these areas are highly responsive to stimulation, and it also takes time for them to learn how to work together.

This research suggests that teenagers tend to view risks differently than adults; they weigh potential rewards much more than possible dangers. And often these perceived rewards are social in nature, tied to peer approval and belonging. So a teen, desperate to fit in with peers who don’t have food allergies and aren’t inclined to support a friend’s difference, might be pushed toward underestimating the risk involved in being exposed to, or potentially consuming, an allergen. Combine this with impulsiveness, and the results can be a dangerous mix.

However, the better news is that teens are far more capable than we often give them credit for. Abigail Baird, a developmental neuroscientist and psychology professor at Vassar College, objects to the stereotypical characterization that teens lack all self-control. “Watch teens at school, hanging out together,” she says. “They have amazing impulse control. But they don’t have a lot of it. They use what they have for their peers, and then they come undone at home.” Impulse control improves with age, and external factors (such as stress, exhaustion or hunger) can cause it to unravel. For parents, the trick is to figure out how to harness the impulse control that adolescents do have and to encourage them to find supportive peers.

This is a significant shift from earlier childhood, when parents tend to focus on protecting kids from potential dangers. To complicate matters, simply talking to teens about risks won’t necessarily change their behavior. “Educating teens is not just giving information,” says Baird. Parents need to give teens room to make more decisions about their lives.

Rather than try to control them, a better approach is to find the incentives to motivate adolescents to act on what they already know. At the same time, Baird says, serious health conditions — such as food allergies or diabetes — should be treated as “non-negotiable logistics”. Parents can help their kids to manage their food allergies responsibly by giving them a more active role and allowing them to decide how they will take care of these logistics.

Respect is fundamental in this process. Baird, who spends a lot of time with teens, suggests parents convey a supportive but firm attitude in conversations: “I don’t want to control you. I want you to control you, but I am ultimately responsible for you.”

Practice, Practice, Practice

Steinberg is a big proponent of focusing on the development of behavioral skills, most of all self-control, as a way of not only reducing risky decisions but also enabling teens to grow up to be healthy, well-adjusted, and successful young adults. The adolescent years provide an exceptional opportunity for nourishing qualities such as self-control, determination, perseverance, and tenacity, which are highly influenced by social environments. Parents and schools need to support kids as they develop these abilities, and provide them with increasing independence as they learn to assume responsibility and do things on their own.

“Kids need to practice,” says Dr. Michael Pistiner, a pediatric allergist with Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates in Boston and co-founder of the educational website Allergyhome.org. “They can work on their skills and communication in a ‘safe space’. Practicing scenarios can be really helpful, for example role-playing how to order and communicate in a restaurant. Coach and guide them to think through managing anticipated situations, such as eating out,” Pistiner says. “Take baby steps, and gradually build them to having increased responsibility.”

This approach proved helpful for Carlin Hanley, 14, who has multiple food allergies and lives in the Boston area. She was shy when she was younger, and struggled with speaking up and reading labels. One spring when she was 10 years old, her family traveled to Maine, and Carlin ordered mashed potatoes at a restaurant. Although the staff said these were safe for her, they likely contained dairy — as she had a reaction. But Carlin credits this as a learning experience.

“It made me realize that I needed to speak up and have more of a conversation. After this incident, my parents told me to try making eye contact and told me to make sure I was specific about exactly what it is that I need.” She mentions realizing that there was “nothing to be afraid of,” and she became more open about her food allergies. Recently, she launched an allergy-friendly food blog and hopes to attract other teens to share advice and stories.

When I asked Carlin what she had been afraid of, she said she was probably afraid of someone yelling at her — though as she got a little older, she realized this fear was in her head and not based on reality. This comment drives home to me how hard it is for adults to know what it feels like to be younger. Although I still remember how terribly awkward and shy I sometimes felt in middle school, the related emotions and fears have subsided with age. Plus, I have the perspective of knowing that this was simply one stage in my life.

Kristen Kauke

Kristen Kauke, a clinical social worker who has run workshops with food-allergic adolescents and is the mother of sons with food allergies, emphasizes this point. “If we assume we know an adolescent’s experience, we invalidate their experience and disrupt our connection with them,” says the expert, who has a practice near Chicago. Rather, we should try to understand how their experience makes sense to them.

“As a teen or tween, perhaps changing schools or sharing about a food allergy is the most significant event they’ve experienced at that point. Everything about teens is in flux — bodies, brains, peers — so feeling stable is a huge challenge. Of course food allergies feel like a big deal!” she says. Actively listening can enable adults to build better relationships based on empathy and validation.

While middle school is a good time for adolescents to learn how to eat away from home and advocate for themselves, high school is a time of brand new friendships, when teens need to develop new strategies for talking about food allergies. The way parents communicate about food allergies from a young age will help to prepare teens for these challenging conversations. Older kids may need to practice articulating thoughts, feelings, and needs.

In her work, Kauke teaches the “D.E.A.R.” strategy: “Describe the situation, express thoughts and feelings, ask for what you need, and reinforce.” For example, if a teenager wanted to enlist the help of teammates after a sports event, the conversation might look like this:

D: “So something about me you might already know is I have a severe food allergy to peanuts.”

E: “Sometimes I feel awkward bringing attention to me when we’re all out celebrating after a game.”

A: “It would be great if while I’m talking with the server, you all kept talking instead of staring at me.”

R: “I appreciate your understanding and help with this.”

Pistiner, meantime, recommends talking through potential scenarios. “We can give them the opportunity to bounce ideas off of us when the pressure is off. Together, we can work through their approach and explore different options,” he says. The allergist is a co-author of Living Confidently with Food Allergy, an online handbook that suggests steps to help teens plan ahead for social situations.

These include collecting menus from local restaurants and calling to speak with staff ahead of time, as well as problem-solving with your teen about how and where they’ll carry emergency medication. It’s also important to introduce several difficult but necessary topics in the context of food allergies – alcohol, drugs, dating and kissing.

Charlotte Jude Schwartz

“Having relationships is the issue that comes up the most!” says Charlotte Jude Schwartz, a teen ambassador for the Bay Area Allergy Advisory Board (BAAAB) who lives in San Francisco, adding that “it’s the most awkward thing.” Charlotte, who’s now 15, got “notes from my mom” and learned to explain how being exposed to peanuts and tree nuts would cause her to go into anaphylaxis, as well as what steps are necessary to help keep her safe.

She also can’t stress enough the importance of finding supportive friends and making use of a “buddy system” so that at least one friend is thoroughly versed in how to manage your allergies. “Talking to your friends in the best thing you can do. If they’re really your friends, they won’t want you to take risks,” she says.

For many parents, the hardest challenge can be summed up with two words: letting go. As difficult as this may be, we have to recognize that it’s ultimately our teens’ responsibility to begin to take care of themselves. “Realistically, I can only offer adequate education of allergy management, and give them room to apply the skills,” says Kauke. “The more I clamp down with control and fear mongering, the less freedom I allow them to develop life skills of their own. No learning takes place in fear.”

Older teens and young adults encounter situations where they have to make decisions in new settings, sometimes far away from home. When Kristen Lilley, a 20-year-old college student from North Carolina, had the opportunity to travel to Australia for a month-long study program, she was eager to go. She and her parents talked with faculty advisers, the airlines, and the travel agent about her food allergies (she has severe allergies to milk and peanuts) so that everyone was mindful of her allergies.

But no one could prepare Kristen for the bar scene in Australia, where the legal drinking age is three years younger than in the United States. Halfway through her trip, she went out with friends, giving her Benadryl to one girl who was carrying a purse and leaving her epinephrine auto-injector in her hotel room. (“I didn’t think I needed it, especially because I didn’t plan on eating anything,” she explains.) After one sip of a “surprise” drink another friend bought for her, she began to have trouble breathing – it turned out to have Baileys Irish Cream. “It was pretty terrifying,” she says. She took an ambulance to a hospital, where her breathing eventually normalized.

Her mom confesses to being “panicked” when she got the call about the incident. After it became clear that Kristen would be fine, she thought “for sure” her daughter would come home. But Kristen stuck it out. “We were very proud of the way she handled being on her own with these challenges,” says her mom. “But we certainly all learned some lessons.”

The Kids Are (Mostly) All Right

Many of the young people I spoke with talked not only about their mistakes, but also their triumphs. Remember Sydney Harris, the student who didn’t mention her food allergies at the Chinese restaurant? After her reaction, she had an epiphany: “I needed to be safe and cautious with my allergies and from there I dedicated my time to being an allergy advocate.” She began a blog, joined the teen advisory panel of Food Allergy Canada, and began to make presentations to teachers at her school. She has also started college and is studying nursing.

Likewise, 18-year-old Juliet Larsen, who lives in Orange County, California, found herself dissatisfied with how she was identified as the “peanut girl” in elementary school. Other kids had bullied her, throwing M&Ms and waving brownies in front of her face. She felt as though she “didn’t fit in.” She decided to fight back, and “distance myself from being the ‘peanut girl.”’ Juliet began to sing in talent shows, act in plays, and play basketball; as she grew older, she began to model and started a food allergy awareness club at her high school.

“I decided never to take risks around food, but to take risks with things that required putting myself out there,” she says. In May 2015, Juliet participated on a teen panel at the national food allergy conference organized by FARE, the research and education organization, where she gave a talk about how to “live your dreams” with allergies.

Juliet and Sydney are among many teens who have drawn positive experiences from life with food allergies. Other extraordinary young people have founded baking businesses, created online and in-person awareness and advocacy groups, produced videos, raised money, spoken at conferences, and even lobbied at state legislatures for stock epinephrine and other food allergy laws.

In fact, there is even new research to suggest that coping with food allergies may help to enable teens to develop a range of skills. At the 2015 annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, Dr. Ruchi Gupta and her team at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine presented preliminary findings of an online survey of almost 200 food allergic adolescents. In a scientific poster titled “Adolescents with Food Allergy: The Good, the Bad and the Beautiful,” they found patterns of risk-taking quite similar to those seen in previous studies, including almost 20 percent of teens willingly eating packaged foods that “may contain” their allergen, and 13 percent admitting they don’t always carry an auto-injector.

Yet participants also revealed remarkably beneficial experiences emanating from life with food allergies. “The teens in our study reported some positive aspects of living with a food allergy: being more responsible (nearly 89 percent of respondents), becoming better advocates (72 percent), and being more empathetic (64 percent) towards others,” Gupta noted in an interview. “Given how the teen mind is preoccupied with everything that’s going on during this age, we should be impressed by how responsible they actually are,” says the associate professor in pediatrics.

These findings resonate with Kauke and her experience working with teens. “So many teens are responsible, but they get so much press for their bad behavior.” Despite occasional lapses in judgment, Kauke routinely finds that teens demonstrate an impressive ability to care for themselves, and that their friends are often quite good at helping them stay safe, too.

The Power of Peers

As I spoke with teens and young adults across the U.S. and Canada, I was struck by how much they know about their food allergies. They understand how to manage their own health (even if they don’t always do it perfectly). Even more, they get what it means to live with a serious chronic condition that can affect almost everything they do. As a result, adolescents with food allergies recognize the institutional and cultural issues that need to change, and many of them have ideas about how to do this. I came to realize that part of our job as parents and adults is to facilitate the ability of young people to join the conversation and enable them to help lead the way.

Gupta’s study tries to tap into this knowledge. Her survey asked food-allergic adolescents what they want, and nearly 86 percent answered: “more public awareness.” In response to questions about schools, the teens surmised that only 11 percent of their classmates would know how to respond during an anaphylactic emergency, despite the fact that they felt that many classmates (48 percent) were generally supportive about their food allergies. More disturbingly, 43 percent of the respondents reported that they felt bullied at some point because of a food allergy.

These findings have convinced Northwestern researchers of the need to collaborate with food-allergic teens and to focus on how their peers can assist them. In a new project, they are asking young people with allergies to help them develop effective educational programs, and Gupta and her team plan to produce peer-to-peer ideas based on this input. In particular, Gupta hopes that teens can provide clues about how to increase the rates of adolescents carrying auto-injectors, whether reaching that goal is about crafting the right messages or developing new technologies.

Even a small act of kindness from a peer can have a big impact. Colby, a 13-year-old from Rhode Island who plays ice hockey, told me a story about one occasion during a tournament when his team went out for dinner. One of his teammates decided to order the exact same “safe” meal as Colby, who has multiple allergies. “This was by far the nicest gesture a friend has ever done for me related to my allergies,” he recalled. “It made me feel great inside.”

The education organization Food Allergy Canada has been an early adopter of the peer-support approach. It has piloted several projects that position teens as mentors, educators and authors. With the help of the teens on its youth advisory panel, the food allergy organization created Why Risk It, a website by and for teens; it features videos on dating and dining with allergies, blogs, and opportunities for visitors to post stories.

The group’s newest project is an e-book, titled The Ultimate Guidebook for Teens with Food Allergies. While doctors have reviewed all of the information, the e-book is completely written by teens. “Given the opportunity, teens have so much to offer,” says Kyle Dine, who is Food Allergy Canada’s youth project coordinator, in addition to his career as a food allergy musician. As well, he notes that teenagers are far more likely to listen to stories and experiences shared by their peers than advice from adults.

When you look around, you begin to realize that adolescents are participating at every level of food allergy advocacy, education and research. For 10 years, FARE has been organizing a yearly Teen Summit in Washington, D.C., where young people from across the country meet and discuss topics important to them. This fall’s summit drew record attendance of almost 400 teens and family members. Meantime, members of FARE’s teen advisory group (called TAG) write articles for the teen blog, advocate, and serve as mentors in all regions of the United States. The Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Connection Team organization also now organizes annual teen conferences, and FAACT is developing a peer-to-peer program for young adults ages 18 to 24, drawing from their perspectives.

And who can overlook the burgeoning number of blogs and Facebook groups being created by teens? In the online realm, young people exchange information and experiences with enviable ease. Ultimately, educating and engaging those incredibly influential peers, as well as less proactive allergic teens, will help to create a stronger safety net for food-allergic individuals. This safety net and social acceptance are critical factors, so that when mistakes happen, the possibility of tragic outcomes is lessened.

This can play out in ways both large and small. Consider the experience of Natasha Dheda, 21, who got into the habit of eating a certain brand of cookies that carried a dairy “may contain” warning label. In her third year at college, she suddenly had an anaphylactic reaction to these cookies. Although she had an auto-injector with her, she felt unsure and hesitated; she had never given herself an injection. Fortunately, she was with a friend. “Having someone with me definitely helped as it was a hand to squeeze when the needle went in!” she says.

A hand to squeeze when the needle goes in. After all the teaching and training is done, what more could anyone ask for?

Heather Hewett is a writer and professor at The State University of New York at New Paltz. She has written on food allergies for major news outlets and the anthology The Good Mother Myth: Redefining Motherhood to Fit Reality.